At Arowana, we founded and scaled up a vocational education company called Intueri Education Group (“Intueri”) which in a period of 4 years became the largest private VET group in New Zealand with a fast growing and highly profitable online business in Australia. Intueri was initially formed in May 2010 with the purchase of a small Christchurch based vocational college called Design and Arts College.

We subsequently executed a buy and build strategy overcoming numerous growing pains challenges, including the debilitating impact of 2 earthquakes in Christchurch, to scale up Intueri from NZ$1m EBIT to NZ$20m EBIT between May 2010 and May 2014.

Intueri was IPOed in May 2014 at a market capitalisation of NZ$235m, with its share price closing 15% up on its first day of trading and subsequently peaking at a 40% premium to its IPO price in December 2014. The IPO delivered a capital gain in excess of NZ$100m for Arowana and we retained a 25% shareholding in the company.

In the ensuing 3 years post IPO, unfavourable regulatory changes in New Zealand adversely impacted Quantum, one of Intueri’s subsidiary colleges that trained second chance learners, primarily of Maori and Pacific Island origin. Furthermore, tougher immigration rules targeting students of Asian descent in particular were introduced which curtailed the growth lever buoying the other colleges in New Zealand.

Meanwhile in Australia, an abrupt tightening of government regulation across the VET sector in the space of 18 months had a material adverse impact on Intueri’s Australian business. This led the group to experience significant earnings deterioration and it was ultimately broken up and sold in April 2017.

We have learned a number of key lessons from this experience:

1 – Minimise exposure to Regulated Training VET models

A Regulated Training ecosystem, as currently exists in Australia and New Zealand is almost by definition politicised which means it is subject to regulatory volatility. In such an ecosystem, education policy is linked to the politically sensitive arena of employment policy (as previously discussed in Part II). So, when macroeconomic conditions change or governments change, there can be significant swings in policy and regulatory conditions.

Intueri felt the full brunt of this in Australia. When Intueri purchased Online Courses Australia (OCA) in February 2014, government policy was highly supportive of private VET providers. At the time, generous VET incentives were in place that were introduced by a federal Labor government in 2012 as part of its strategy to drive vocational education.

This was replicated at state government level especially Victoria, which also had a Labour government at the time. With the benefit of hindsight, regulatory settings were too generous as reflected in relatively lax rules around course fee levels (no caps), completion rates (no minimum levels) and other aspects of training delivery. As a result, there were a handful of rogue operators that took advantage by overcharging for courses, enrolling unsuitable students and failing to achieve acceptable completion rates.

A new Liberal / Conservative federal government was elected in September 2015 and uncovered an estimated US$2.5bn budget blowout. This coupled with negative media headlines on certain rogue operators prompted the federal government to swiftly tighten regulatory settings. In October 2016, OCA along with numerous private players had its licence to deliver VET courses and government funding revoked despite the fact it had previously passed all government audits. The regulatory goal posts had changed and done so abruptly.

By October 2017, an estimated 80% of the private VET FEE-HELP providers that were in operation 4 years prior had their licences revoked in what was effectively a government “blitzkrieg”. In February 2018, the second largest VET player in Australia, Study Group, owned by the US private equity fund, Providence, had its licence revoked, meaning a clean sweep of the top 3 largest players was completed. The regulatory pendulum had swung from very lax in February 2014 to ultra-tight by February 2018.

Unfortunately, Intueri had a similar experience in New Zealand primarily in relations to Quantum, which was the largest college in the group. Before announcing its purchase of Quantum in late February 2014, Intueri’s business was of a similar size from a revenue and profits perspective. When it was approached to buy Quantum in September 2013, it was clear that such an acquisition would create by far the largest private VET group in New Zealand.

As a result of its rescue of and commitment to the earthquake damaged D&A College business in Christchurch and subsequent purchases of other VET colleges in New Zealand, Arowana had always maintained a cordial and open relationship with the key education regulators in New Zealand. The TEC (Tertiary Education Commission) and NZQA (NZ Qualifications Authority) had been engaged regularly and they had been consistent, commercial and forthright in our dealings with them, as we were also.

As part of its ongoing engagement with the TEC in particular, Arowana had been informed by the TEC that the two issues that it was particularly sensitive towards were (i) excessive use of gearing – which we did not engage in and (ii) foreign ownership – and they considered Arowana to be a foreign owner.

Our due diligence process was typically rigorous (or so we thought) and encompassed the following elements:

Industry expert consultant – since prior to our initial entry into the NZ market in 2010, we had engaged the services of an industry expert consultant who formerly worked for the TEC as a regulator and as a result had deep knowledge of all the players in the industry. Before we considered an investment in any college business in NZ, we would always consult with him.

This consultant was always incisive in his assessments and we rejected the opportunity to invest in dozens of colleges and ultimately had only invested in 5 colleges in NZ including Quantum prior to Intueri’s IPO. He was invited to join the board of Intueri prior to its IPO and his presence on the board gave it significant credibility with the regulators in particular.

Face to face meeting with regulators – in January 2014, Arowana had meetings with both the TEC and NZQA in Christchurch at meetings orchestrated by the industry expert consultant. In both meetings, upfront permission was sought and granted to take the respective regulators across the Chinese wall in relation to Intueri’s deliberations to acquire Quantum and then progress to an IPO on the NZ stock exchange. The purpose of the meetings was very specifically to seek the view of the regulators in relation to the following issues:

Did the regulators have any issue with Quantum as an education institution? – No issues were raised by the regulators in relation to the Quantum college and business (this was confirmed by the TEC audit report – see below).

Would the regulators have an issue with Intueri acquiring Quantum? Given the acquisition would make Intueri by far the largest privately-owned provider in New The regulators again raised no issue and we were encouraged to continue to consolidate what they considered an overly fragmented market which made their jobs more difficult from a regulatory standpoint.

Finally, would the regulators have an issue with Intueri seeking an IPO on the NZ stock exchange – again no issues were raised by the regulators. Rather, they indicated they would be pleased with such a move if it meant Arowana, as what they considered to be a foreign owner, would be reducing its shareholding to a minority level and that Intueri (including Quantum) would be majority NZ owned as a result of any IPO.

TEC audit report – The TEC as part of its regular compliance program, had actually undertaken a comprehensive regulatory audit on Quantum in 2013 and its final audit report was handed down in December 2013, only 2 months prior to Intueri’s acquisition. No material issues were raised by the TEC in relation to Quantum in this audit report (which was publicly available).

Acquisition due diligenceencompassing commercial, operational, human resources, IT, accounting, legal and tax issues. A cohort of reputable and suitably qualified local experts were engaged to conduct due diligence for and on behalf of Arowana.

IPO due diligence – a second round of independent due diligence was conducted by an experienced and reputable team of bankers, lawyers, auditors and investigating accountants as a mandatory prerequisite to the IPO of Intueri.

Furthermore, the IPO prospectus was reviewed and vetted by the relevant regulators being the Financial Markets Authority (FMA) and the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX) with a number of Q&A rounds and iterations of the prospectus based on feedback from the regulators (including detail such as text placement and font)

What we thought was a very robust due diligence process was however not enough to mitigate against what ultimately unfolded. We were perhaps naïve to rely on what a government regulatory body says directly in a face to face meeting nor should we have placed reliance on the comprehensive audit report issued by the regulatory body on the Quantum business just 2 months prior to the acquisition.

Despite conducting 2 rounds of rigorous due diligence involving external accountants, auditors and lawyers as well as having an industry expert consultant who formerly worked for a NZ regulator, this was ultimately not enough.

Following some negative articles in NZ’s financial press in 2015 including one criticising NZ’s education regulators in relation to Quantum, the TEC commissioned Deloitte in November 2015 to undertake a forensic investigation into Intueri and Quantum. Deloitte conducted an extensive range of interviews including of present and past board and staff members of Arowana, Intueri and Quantum.

Deloitte delivered its draft report to the TEC in September 2016, but the final report was only released the week before Christmas 2017. It is to be noted that both the FMA (Financial Markets Authority) and the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) of New Zealand had also been called into action to investigate the IPO of Intueri and its acquisition of Quantum; the former did not raise any material issues and the latter’s investigation was dropped.

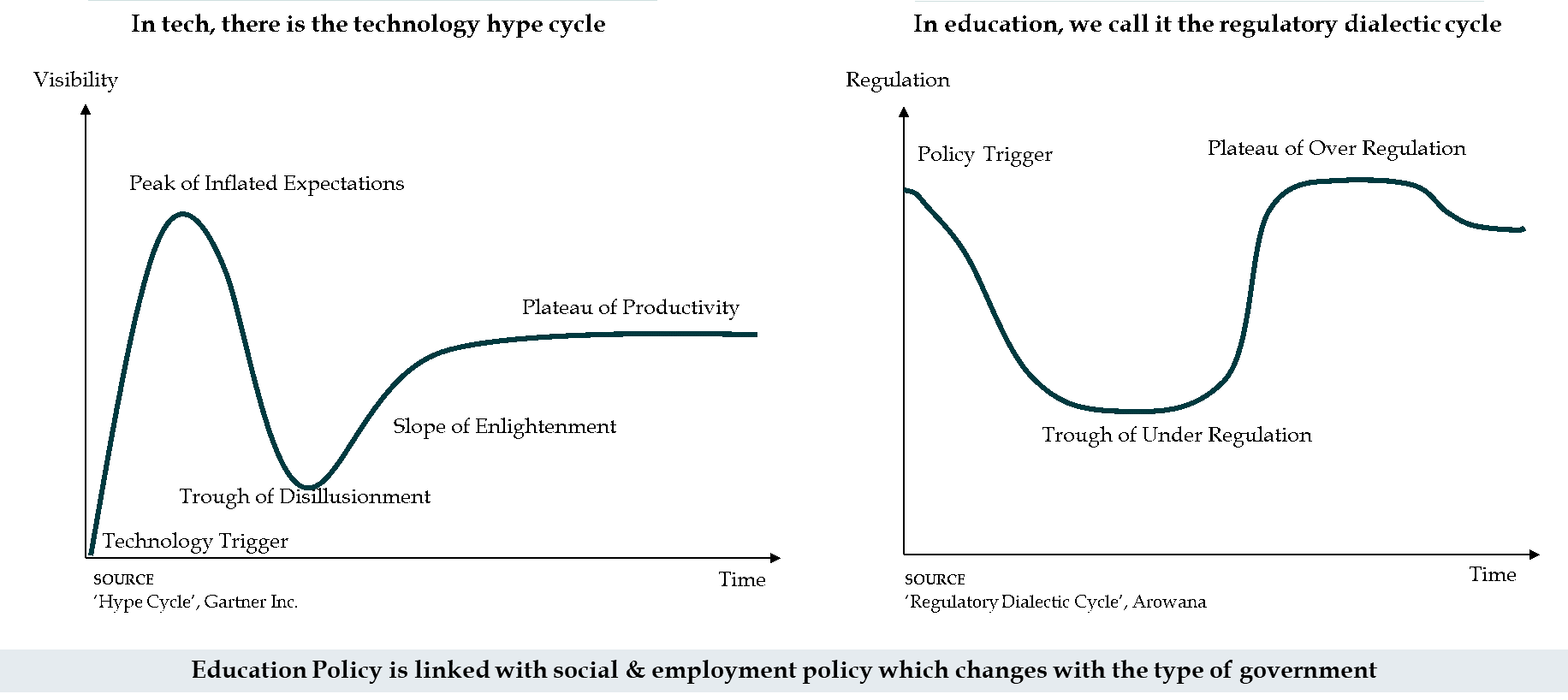

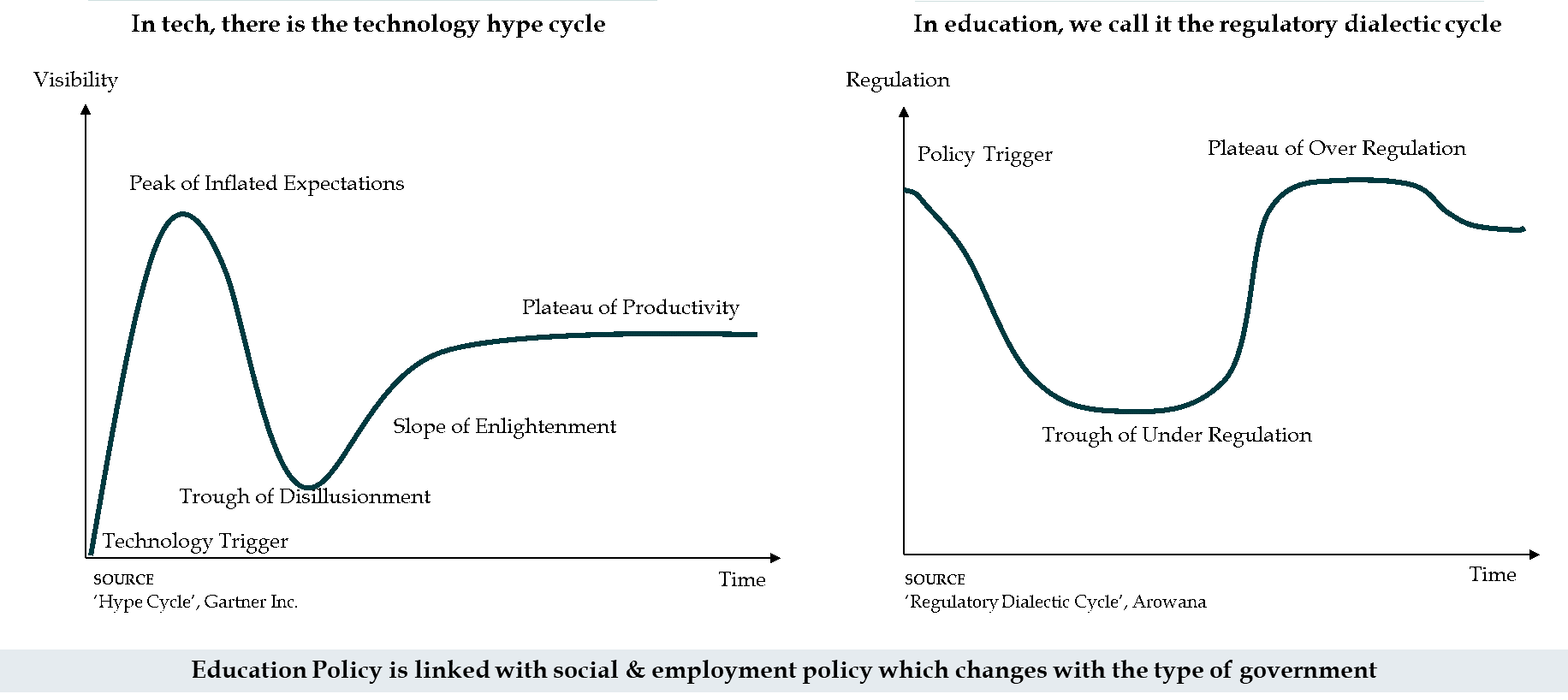

While our Intueri experience demonstrates that minimising exposure to Regulated Training VET businesses is prudent, we are not suggesting that they are categorically un-investable. In fact, there is an optimal time to invest in such businesses. This moment in time is what we call the “plateau of overregulation” which forms part of the regulatory dialectic cycle (see diagram below). It is when regulations have been tightened too much and overreached.

In such times, VET businesses can potentially be purchased at “out of favour” valuation multiples that overcompensate for the regulatory risk. Subsequently, what tends to happen is that the regulatory overreach is adjusted within 2 to 3 years and operating conditions normalise. In short, opportunities can present themselves to purchase these types of VET businesses at trough valuation multiples on trough earnings.

2 – Maximise exposure to employer led and fee for service VPET models

As we have seen from the Part II discussion on VET models, the “gold standard” is the dual VET model practised in Switzerland. The reason for its success is the heavy involvement of employers in curriculum design and teaching delivery. Importantly, the delivery is primarily through on the job workplace training and this ensures skills taught are relevant.

Some VET courses lend themselves better to this type of delivery model because they are more tactile in nature; such as carpentry, traffic control and hairdressing. However, in a Regulated Training ecosystem, politics can inadvertently or deliberately prevent such a delivery model being effective in practice.

For example, Intueri owned the largest hairdressing college in the country. Hairdressing businesses routinely complained about the lack of suitably qualified staff, which could have been solved by hairdressing trainees undertaking training on the job. But long standing political rivalry between government regulated training colleges and an industry driven apprentice training body stymied this from happening systematically.

It has taken Switzerland the best part of 30 years to get to its current VET system and culture, so this will not happen overnight in countries that do not practise a dual VET model. Outside of Europe, there is only South Korea that practises a proper dual VET model.

However, as noted in Part II, we are of the view that Singapore will rapidly execute on its new VET strategy, modelled on Switzerland and become a global leader within the next decade. As a respected education thought leader in ASEAN and China, we expect the Singapore model will influence policy makers in these countries to embrace and similarly apply a dual VET model (as has happened in other areas of education).

In addition to employer led VET business models, there are also fee for service VET models where students pay their own tuition fees, without any government subsidies or incentives. These are often the most attractive education businesses, because the students are confident of a job outcome that will deliver a sufficiently attractive return on invested fees and time that they are prepared to pay for it themselves.

This category includes international fee for service students that attend VET colleges in countries like Australia, Canada, Singapore and New Zealand. Typically, these VET colleges also cater to domestic students but on a subsidised basis.

(3) Focus on larger addressable markets with diversity of skills shortages and deep management talent pools

Skills shortages can be cyclical as exemplified by the peak mining boom years of 2010 to 2012. In commodity countries like Australia and Canada, this caused all types of outsized and somewhat perverse skills shortages.

For example, McDonalds in the mining town of Mackay in Queensland, Australia had to import store managers from the Philippines because all of the locals had gone to work in the mines. There was such a chronic shortage of electricians that it caused a bubble in pay, with “sparkies” as they are known in Australia were earning between US$100,000 and US$300,00 per annum, significantly above normal levels. Fast forward to 2018 and this situation has normalised.

We believe however that this is a window into the future of skills gaps – skills shortages will rapidly manifest but will tend to have a shorter half-life mirroring that of shorter industry and company lifecycles, thanks to an ever increasing pace of technological disruption. A VPET business will not be able to survive let alone scale by focusing on one or two skills areas, but must instead have a portfolio of skills that it covers and trains for.

Furthermore, an effective VPET group will not only need to be adept at predicting future skills gaps but also have a culture of pace to develop courses quickly to train for such skills shortages. For example, the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) estimates that the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will trigger a need for more than 75,000 data protection officers (DPOs) globally within the next 2 years. This is a brand new role that has been created and defined by GDPR and initially there will be a mad scramble for the very few suitably qualified DPOs that currently exist.

However, within 3 years, it is likely that most of this skills gap will have been largely filled as companies, VPET businesses and data professionals alike rush to meet the demand. Interestingly, prior to the introduction of GDPR, Germany and the Philippines were the only countries that had mandatory DPO laws. For the Philippines, I believe GDPR is a significant strategic opportunity as it tries to work out how to combat the existential threat to its Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry posed by artificial intelligence (both machine learning and deep learning).

Also, in markets where private VET businesses have only been a relatively recent development, it can be difficult to find suitably qualified general and technical managers who balance strong teaching pedagogy and commercial nous. This balance is important to ensure a VET business is delivering strong teaching outcomes in a profitable and sustainable manner.

If a leadership team is overly focused on quality outcomes and compliance, it can lead to a situation where a business is unprofitable. Conversely, if a leadership team is too focused on maximising shareholder profits, this can lead to poor teaching outcomes and /or compliance breaches. We experienced these challenges first hand with Intueri where it was compounded by the fact that the group was experiencing strong scale up growth during Arowana’s ownership (which can stretch the best of management teams).

4 – Focus on markets where government & society do not consider VET inferior to tertiary education

In building Intueri, we experienced firsthand how VET can be treated as a “second class citizen” by education policy makers, bureaucrats and regulators alike, inferior in their minds to tertiary academic education. This will never be voiced publicly especially when there are minority interest groups involved but it is felt when you are operating within the industry.

Simon Bartley, the President of World Skills, believes that “governments around the world are beginning to actually say that we need a mix-skills economy. Yes, it is good to have graduates, post-graduates, Ph.D, doctorates, but much of the work which needs to be done to make our society, industry and business work is actually done by highly qualified technicians, craftsmen and professionals in those areas. I think that realisation is meaning that policies of governments are changing.”

Such a mindset has been common in many countries over the past 40 years as they strived to improve education standards. In this regard, the percentage of a population with a university degree was considered the key measure of success. However, the percentage of university graduates globally that do not have a job in their field of tertiary study has increased significantly in the past decade.

We have all met the career bartender or waitress with a masters degree in a restaurant in New York, a café in Sydney or a bar in London. Meanwhile at the same time, more employers are lamenting the inability to find staff with practical vocational skills and this “skills gap” has resulted in high levels of youth unemployment globally.

More progressive governments and education policy makers have recognised the mindset above as antiquated and sought to address it. In Switzerland, the public sector, the private sector and society at large accord equal merit to both academic and vocational routes. This is also the case in Germany, Austria and Denmark and has been the case for many years.

Former Swiss President Johann Schneider-Ammann argues that “Vocational training is the “backbone” of the education system and the Swiss economy as the skills acquired through vocational training are those that are demanded by the labour market.”

More recently, Singapore is an interesting case study. Singapore society is built on a Confucian mindset and attaining a university degree has been the “holy grail” for parents and students in this 60-year young nation. However, over the past 5 years, the Singapore government has recognised the skills gap issue and the threats posed by the Fourth Industrial Revolution and an aging population.

It has worked to change the lowly perception of VET amongst general society, teachers and students alike by modernising ITE (Institute of Technical Education) campuses, increasing the range of curricula and introducing an Earn and Learn model. The results have been impressive with ITE’s brand equity score jumping from 34% in 1997 to 68% in 2015 reflecting a much improved perception of VET amongst Singaporeans.

Investing in and operating a VET business in markets where there is an inherent elitist bias against VET presents greater risk of disadvantageous regulatory settings and adverse budget allocations. It is important to be able to recognise and mitigate against such risks.

Our strategy and execution plans with regards to scaling up EdventureCo have been heavily influenced by the lessons learned above. In a period of less than 2 years, EdventureCo has become one of the largest private VPET businesses in Australia as well as the broader Asia Pacific region.

It has less than 10% revenue exposure to the Regulated Training ecosystem in Australia with the balance of the business not exposed to regulation nor in receipt of any government funding. EdventureCo’s vision is to build an Asia Pacific leader in vocational and professional education and training (VPET).

Across all of its curriculum, EdventureCo works with employers and industry to design and deliver curricula that is relevant. Relevance to employers is key to ensure successful job outcomes. Our mission is to deliver relevant skills first and qualifications second, enabling students to upskill and reskill, addressing the skills needed tomorrow, today.

Whilst its business is largely Australian centric today, EdventureCo is focused on growth and skills shortage opportunities in selected markets across Asia, in conjunction with suitable local partners.

This piece concludes a series of 3 blogs on vocational training. Learn more at Arowana.