International approaches to delivering VET

As a result of nearly a decade of being an investor in and operator of vocational education colleges, the team at Arowana have studied various models of delivery being practised globally.

There are essentially 4 models of vocational education and training being practised around the world: Dual VET, School-Based VET, Career Education and Regulated Training

The essential difference between each model is who holds the balance of power in designing curricula and delivering vocational education programs: the government (through its education and/or employment ministries) or the private sector (employers and trade associations).

The Dual VET model is primarily driven by the private sector while in a Regulated Training ecosystem, the government is the key player. This has important ramifications for the effectiveness of the different models, as discussed below.

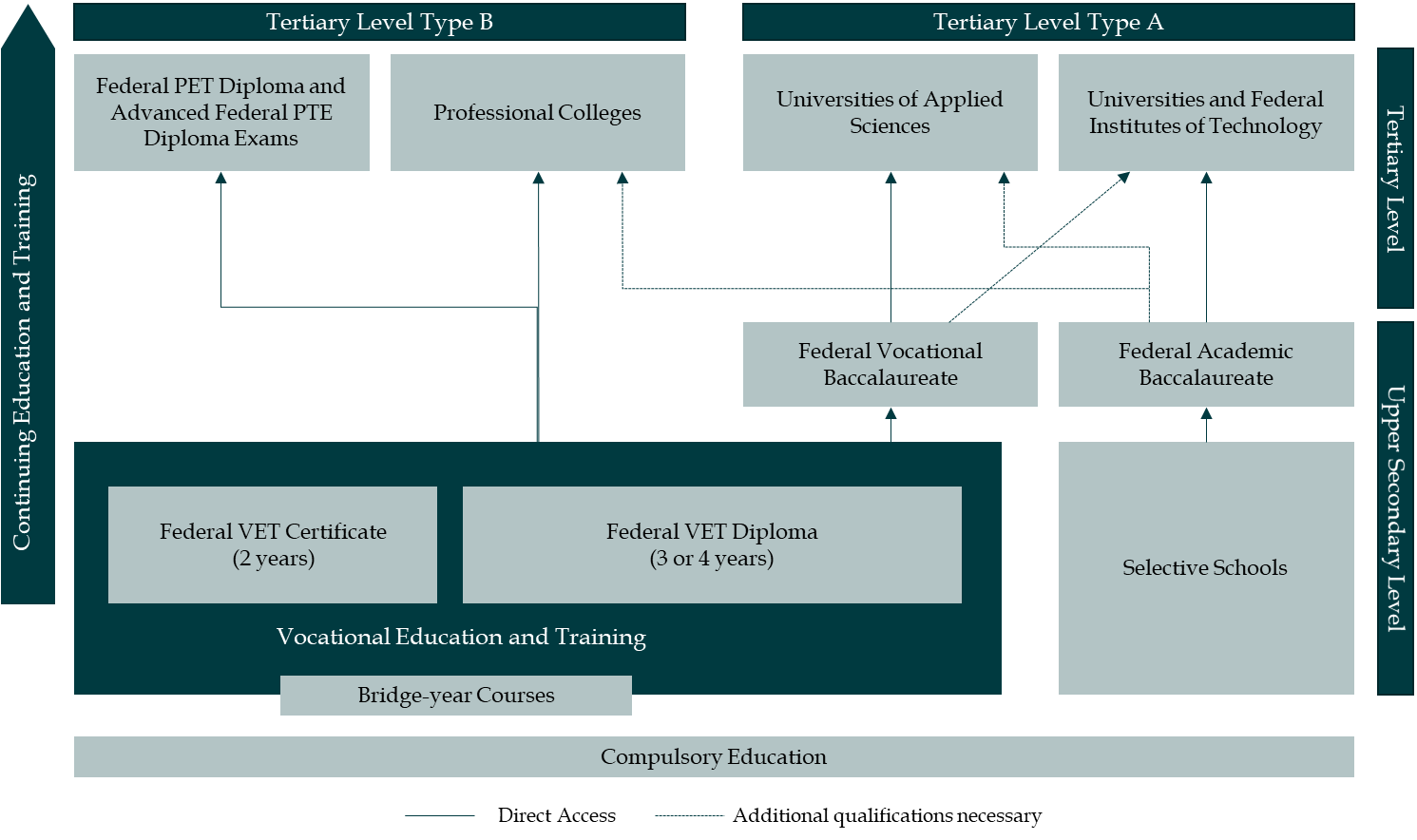

Switzerland (as per diagram above), Germany, Austria, Denmark and more recently South Korea operate a Dual VET model.

Duel VET in Switzerland

The key features of a Dual VET model include “Earn while you learn” apprenticeships focused on workplace on the job training. In Switzerland, 15 to 16 year old students who are about to complete the compulsory school education system have a choice of two main options for the continuation of their education and training: VET or general education (the latter with a view to going on to an academic tertiary pathway). Two-thirds of Swiss students choose a VET program.

A typical VET program would involve doing a 2 to 4-year apprenticeship and combines classes at a vocational school with on-the-job training at a host company. Therefore, it is called a dual VET model. On average, a Swiss VET student spends between 60 to 80 percent of their time in workplace learning under a work contract. Upon graduation, apprentices receive a nationally recognised VET diploma.

During the program, the host company pays the apprentice a salary, which increases with each completed year. The concept of earning money while still getting an education is a significant incentive for future apprentices.

Salaries vary depending on the occupation and are lower than what regular employees would earn. From an employer’s perspective, they benefit from lower cost labour that is being skilled up in a practical and relevant manner that suits their requirements.

The schemes involve public private partnerships where the private sector primarily drives curricula design and funds delivery. Professional organizations (employers and trade associations), cantons (state governments) and the Swiss Confederation (federal government) collaborate closely to define curricula, skill sets and standards for various occupations nationwide.

In a dual VET model, the government and trade associations recognise that the most important partner is the private sector and it is employers and trade associations that lead the charge in both design and delivery of curricula.

It is these companies that employ apprentices and provide on-the-job education and training, and also pay for the courses attended by apprentices. In the process, they provide approximately 60% of the funding for a VET student. They are also responsible for leading the continuous updating of the content to achieve the relevant qualifications.

The cantons are responsible for funding the VET schools as well as career services and teacher training, contributing approximately 30% of the cost of funding for a VET student. The Swiss Confederation is responsible for quality control, compliance, transparency and system strategic development and effectively contributes 10% of the cost of funding for a VET student.

The permeability of education pathways to enable “lifelong learning” is a critical aspect of a dual VET system. The Swiss system intentionally provides many pathways to allow students to move seamlessly between academic and vocational studies as well as seamlessly from VET on to higher education at a university of applied sciences.

As a result, there is almost complete permeability that enables students to undertake continuous learning and training in VET or tertiary programs. For example, when an apprentice graduate, a student can elect to take additional classes (leading to further accreditation) at a professional college or even choose to embark on a tertiary university qualification.

The fact that you chose a VET pathway at 15-16 years of age does not preclude you, later in life, from pursuing a university degree in future, or vice versa. It is also very easy to completely change one’s professional field.

School Based VET in Finland

Finland consistently ranks as one of the top 3 in the world for its education system and outcomes. It operates a School Based VET model as does Poland, Slovenia, Lithuania. This model is like the Dual VET model but the key difference is that most of the training is delivered in a classroom setting as opposed to in the workplace.

The key features of a School Based model include curricula delivery more focussed on classroom based training. In a school based VET model, an apprenticeship style contract between a VET student and a private sector employer is atypical.

Most of the delivery is done in classrooms and whilst the percentage varies from country to country, this usually represents more than 50% of the program. However, at least some of the delivery will be conducted in a workplace environment.

As is the case with a dual VET model, the private sector drives the design and updating of the curricula but not its delivery. This confers the benefit of ensuring skills are relevant and contemporary, as is the case for a dual VET program. However, the private sector is less active in the actual delivery of programs. Funding is primarily from the public sector in the form of subsidies.

Career Education in Singapore

Singapore has traditionally practised a Career Education VET model with its Institute of Technical Education (ITE) and polytechnics as the centrepiece. The key features of a Career Education model include curricula delivery exclusively focused on classroom based training.

Singapore’s ITE and Polytechnics have curricula that look very similar to tertiary programs. Program tenures are typically 2 years and already enrol 60% of all post-secondary students. Workplace training only takes place after the completion of classroom curricula delivery.

The public sector drives curricula design and delivery with some input from private sector. While private sector employers and/or trade associations might be consulted or serve on boards, curricula design is fundamentally in the hands of the government’s education and/or employment bodies in a career education VET model.

The relevant bodies also dictate delivery of curricula by setting rules and regulations. Funding is government subsidised by 85-90% for Singaporean citizens and 40% to 50% for permanent residents, with international students paying on a full fee for service basis.

This system is characterised by a lack of permeability across education pathways. VET accreditations in a career education VET model are generally non-transferable, which limits the capacity for lifelong learning and workforce agility.

It is to be noted that Singapore has been reviewing its VET strategy and recently introduced a range of new VET initiatives including an Earn and Learn program. Back in 2015, the Singapore government acknowledged that it needed to learn from and embrace more of the Swiss “gold standard” dual VET model and change the culture of education design and delivery as well as society’s view of vocational education.

Led by its Deputy Prime Minister, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Singapore has been studying the Swiss VET model with a view to future proofing its economy by dealing with a tight labour force and the increasing rate of change of skills in the modern workforce.

Singapore is now actively championing lifelong learning through upskilling and reskilling with the SkillsFuture Singapore (SSG) agency tasked with driving what is known as the SkillsFuture movement. An annual budget of S$1 billion per year to the year 2020 has been committed by the Singapore government to the SkillsFuture program.

SSG will also soon launch new programmes for the Continuing Professional Education and Training (CPET) segment to help adult education professionals make learning even more relevant and accessible through its Institute for Adult Learning programme.

Given its foresight and focus, we would not be surprised if within the next decade, Singapore will have one of the world’s best and most effective VPET programs.

Regulated Training in Australia and New Zealand

Both Australia and New Zealand have VET models that are now primarily Regulated Training ecosystems. The key features of a Regulated Training model include the fact that the public sector regulates and dictates both curricula design and delivery.

In a regulated training environment, the government is the key player and there is limited input and engagement with the private sector.

Curricula is developed through a multi-layered approach but vetted in accordance with a regulatory framework that focusses on protecting participants (in other words the compliance imperative is the primary objective as opposed to relevance).

The many layers of bureaucracy mean that changes to curricula or developing new curricula are extremely slow and in areas where technology is changing the nature of work, is often out of date by the time it is released for training.

There is no consistent or best practice model for the delivery of training with government funding being primarily directed away from workforce training and towards state-owned training centres that favour classroom based training and tend to be detached from industry.

Training subsidies are provided for the private sector in the form of cash payments and/or payroll tax rebates to incentivise companies to take on apprentices and trainees are a feature of a regulated training model.

However they tend to focus on lower level qualifications creating a funding gap for those students who wish to level-up their qualification. They can also prevent students from undertaking more than one funded course meaning students are stuck in the occupation or qualification they first choose with no funded ability to move sideways.

Student loan schemes are also a feature of some regulated training models to incentivise vocational education and training participation. These involve qualifying students being granted a government loan to undertake vocational education courses, which is to be paid back upon achieving a minimum level of income in the future.

The key problem with a regulated training model is that it risks obsolescence and irrelevance because it does not involve employers in a meaningful way in the curricula design phase. The practical reality is that it is employers who know best when a curriculum needs updating and what needs to go into a redesign well before education system academics, regulators and bureaucrats do. Furthermore, employers will move with greater pace and agility because they are incentivised to do so.

So what happens when you have apprentices and trainees who are obsolete in the eyes of employers? You get sub optimal employment outcomes, a continued lack of skills development and a lot of wasted money, time and effort.

When the public sector (regulators, bureaucrats and academics) have all the power, the result is a VET model that has a tendency to ignore the needs and opinions of employers and students. This leads to a number of common VET program struggles, such as a mismatch between the education students receive and the skills that the job market requires.

For example, a major American city once offered VET in horse-shoeing, yet the city was not known for its horse population. This mismatch can also lead to an over or undersupply of certain occupations. Most commonly though, academic style programs tend to lack sufficient nexus to actual skills needed by private sector employers, with limited opportunity for practical experience and major challenges finding skilled teacher-trainers.

Students learning practical content in classrooms might not get the right mix of skills, or find out too late that they do not enjoy working in an occupation. Public sector educators and bureaucrats cannot know how and when to update curricula as technology and demand changes. And when they do, they move too slowly so that by the time the new curricula is released, it is already outdated.

So why persist with a Regulated Training model when there are proven alternatives such as the Dual VET model? The answer is politics. In particular, the key benefit of a regulated training model is that it enables the implementation of “labour market integration” strategies for at risk individuals including the long term unemployed.

The sceptic would say this means a regulated training model equips governments with a calibration tool to “manage and massage” the politically sensitive unemployment rate including the NEET (not in employment, education and training) rate. In short, the more people ostensibly in training that would otherwise be unemployed, the lower the unemployment rate and NEET rate.

This post is the second in a series of three. Read the original post and find out more at Arowana.

Kevin Chin is the founder and CEO of Arowana. He has started, operated and sold businesses offering software, education, funds management, media, infrastructure services and solar power and led 5 IPOs in the last decade across the NASDAQ, ASX and NZX exchanges.